Gearing up for the next round of micro-internships in Trinity Term 2021, the Heritage Partnerships Team is pleased to feature this blog post by Cleome Rawnsley. Alongside two more interns, Cleome completed a micro-internship with the Manar al-Athar photo archive in Hilary Term 2021. The Heritage Partnerships Team co-hosted this micro-internship, which was set up in close collaboration with the Careers Service of the University of Oxford.

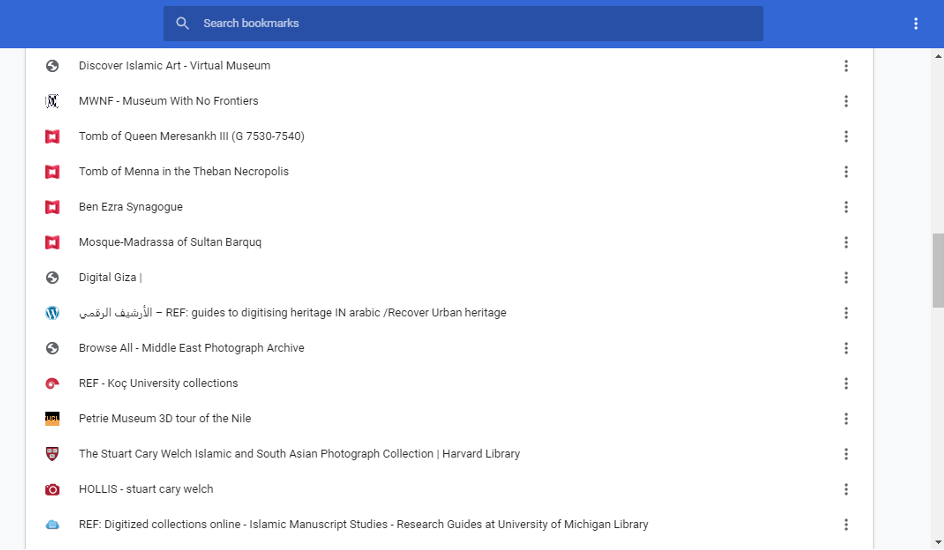

I responded to the call for research and strategy interns with the University of Oxford-based Manar al-Athar photo archive because I wanted to see for myself what kind of work goes into producing such an interesting project. Over just five days I was able to contribute to the archive’s operations by researching the strategy, scope and accessibility of digital heritage resources based in or focussing on North Africa. Working primarily with Miranda Williams and Katerina Vavaliou, as well as two other graduate interns, the internship became a wonderful way of learning new skills while also meeting and interacting with new people working in fields rather different from my own - opportunities which have otherwise proved hard to come by in the last year or so.

I started my internship by combing the internet for any and all digital heritage resources hosted online treating North Africa that I could find. Even in the very first stages of my research, I started to realise key things about the landscape of digital heritage across the region - namely, the fact that digital resources on or from Libya are unfortunately lacking and that resources based in the countries of the Maghreb are just recently experiencing a revitalisation. It felt very satisfying to be able apply my reading skills in both Arabic and French to my research work, but nor were these abilities essential for the work being done: an interesting, but not entirely surprising, aspect of the resources coming out of the Arabic-speaking world is that they are variably delivered in Arabic. In the Maghreb, where, until now, digital tools for learning about immovable heritage have almost exclusively been produced by national ministries, French dominates as the language in which resources have been delivered and their data recorded. A mobile-phone app developed by heritage researchers in Tunisia, however, represents a recent and welcome example of an innovative digital resource that is delivered in Arabic and English as well as French.

The number of very sophisticated 3D resources on Egyptian archaeology, such as those that allow ancient monuments to be explored from the comfort of one’s own home, have almost all been primarily developed and delivered in English, an effect of the long-standing institutionalisation of Egyptology in universities based in the US and the UK. Despite the short length of the internship, the research I undertook during it allowed me to reflect much more upon the issues of colonial legacy and cultural hegemony in heritage than I thought I would have been able to, and in the way I found most interesting - through the lens of language.

I found it incredibly useful to collaborate with my co-interns through collating our research findings on documents, thinking through obstacles to our research together and checking in with each other regarding our progress. As the end of the week neared, it was time to start focussing on the content for my report on the landscape of digital heritage in my assigned region and on how best to present my findings. My presentation, delivered on the final day of the internship to the Manar al-Athar team and my fellow interns, focussed on the various linguistic and cultural contexts in which digital resources on North Africa are embedded and how these may inform the impact and reach of the resources for audiences both in and external to the region. Throughout the internship, I felt supported by the Manar al-Athar team, but also that I was entirely trusted to plan and carry out quality research by myself. We were encouraged to offer ideas and recommendations regarding how they deliver the photographic resources that they hold. Before starting the internship, I wouldn’t have expected this kind of work with such senior and specialised researchers to feel so collaborative.

I would absolutely recommend Manar al-Athar as an organisation to intern with. They are a welcoming, enthusiastic team of people whose work is continually advancing and whose projects extend in interesting and unexpected ways. Even though my academic background is not in heritage or archaeology, there wasn’t a moment that I felt out of my depth; rather, I felt enthused by the opportunity to learn more from my supervisors and peers with each step of my research.

Cleome Rawnsley (she/her) is an MSt student in Comparative Literature and Critical Translation who works with French, Arabic and Spanish. She is currently researching experimental Canadian feminist writing, using feminist philosophy to interrogate its conception of femininity and womanhood.

To find out more about this micro-internship project read a blog post by Noah Cashian here.

Manar al-Athar Photo Archive

Oxford University Careers Service

TORCH Heritage Programme